Why Not Lottocracy?

Democracy Without Elections

Democracy tends to perform better than the alternative systems we have tried. But the other systems we’ve tried have been awful, so it is a low bar.

—Jason Brennan, Debating Democracy

Around the world, democracy is frequently regarded as the gold standard for governance. It represents a collective effort to shape our futures in a way that reflects the will of the people, ensuring that every voice can be heard and every vote can have an impact.

But this noble vision faces numerous challenges. Public ignorance hinders the electorate’s ability to make informed decisions. Partisan bias distorts citizens’ perceptions of reality. Polarization erodes the mutual understanding needed for cooperation and compromise. There is declining trust in experts, politicians, and fellow citizens. Democracy itself is in crisis, or so we are constantly told.

Given these challenges, it becomes crucial to reconsider the future of democracy or, even more radically, envision new models of governance altogether. In this post, I want to consider two new versions of an old idea: sortition—or random selection.

The Case for Sortition

Democracy is usually associated with voting and elections. But from a historical perspective, democracy is more closely tied to sortition than elections. In ancient Athens, many public offices were filled through random selection because elections were seen as aristocratic. Aristotle notes, “The appointment of magistrates by lot is thought to be democratic, and the election of them oligarchical.”1 Nearly 2,000 years later, Montesquieu took for granted the association between sortition and democracy.2 This method was based on the belief that all citizens had an equal right to office and that random selection is more impartial than elections, which tend to favor the wealthy or well‑connected.

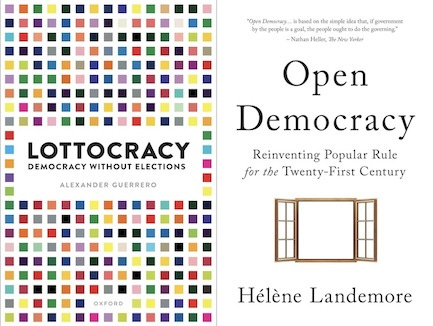

I want to focus on two recent proposals for introducing sortition in democracies: Alexander Guerrero’s lottocracy and Hélène Landemore’s open democracy. I’ve chosen to focus on these fully lottocratic systems for two reasons. First, it is doubtful that modest lottocratic proposals, such as advisory panels, can overcome the epistemic dysfunctions of electoral democracy. To overcome the problems of ignorance, irrationality, and polarization, and to avoid the distorting influences of partisanship, elections, and money in politics, I think we must consider the daring idea that democracy can do without elections, politicians, and political parties. Second, as Guerrero notes, it is useful to consider the possibility of full legislative replacement as a kind of thought experiment, to more clearly highlight the advantages and disadvantages of lottocratic institutions in comparison to electoral institutions.3

Lottocracy

In light of epistemic concerns with contemporary electoral systems (e.g., voter ignorance and distorted information environments), Guerrero suggests that we reconceptualize democracy to stop equating it with electoral representative democracy. He does not advocate abandoning democracy, understood as egalitarian rule by the people. Rather, he proposes a lottocratic system that can overcome the “epistemic pathologies” of electoral representative government.

The key features of Guerrero’s lottocratic legislative institutions are:

Single Issue: Rather than a single generalist legislature, in a lottocratic system there would be many single‑issue legislative bodies, each focusing on one policy area or sub‑area (e.g., agriculture, immigration, health care, and education).

Lottery Selection: The members of each single‑issue legislature are chosen by lot from the relevant political jurisdiction.

Learning Phase: The members of each single‑issue legislature hear from experts and stakeholders on the relevant topic during each decision‑making session.

Community Engagement: The members of each single‑issue legislature have dedicated time for discussions and consultations with the public, including activists and stakeholders who would be impacted by the proposed actions.

Direct Enactment: The members of each single‑issue legislature possess the ability to either implement policy directly or implement policy in collaboration with other single‑issue legislatures, provided it is jointly authorized.4

These single‑issue, lottery‑selected legislatures are called “SILLs.”

Guerrero imagines there will be approximately 20 different SILLs, each focused on a specific policy area, such as agriculture and nutrition, education, energy, health, transportation, military and defense, environmental protection, market regulation, trade, immigration, and workplace safety. This network of SILLs would be responsible for creating most laws and policies. Each SILL would have 300 members chosen by lottery from the relevant political jurisdiction. They would serve 3‑year terms, with the terms staggered so that 100 new people start every year, ensuring a continuous cycle of renewal. There would be no legal requirement to serve, but the financial incentives for participating would be substantial. There would also be measures in place to adjust for family and work commitments, including relocation costs and legal protections so that individuals are not penalized professionally for serving.

The salary would be contingent on SILL members avoiding any prohibited interactions with interested parties during their tenure. They must also refrain from accepting money or other forms of benefit before or after their service, with ongoing surveillance to ensure compliance. Finally, there would be some mechanism to remove people for misconduct, including failing to attend meetings, showing up drunk, and speaking out of turn.

Each SILL would meet for two legislative sessions per year, and the structure of each meeting would proceed roughly as follows. First, the SILL would decide the agenda for the next session by a process of agenda setting. Second, there would be a learning phase in which the SILL hears from experts for each item on the agenda. (There would also be a process to determine who counts as an expert and which experts are invited to speak.) Third, SILL members would begin the process of developing and deciding upon legislative proposals. This will likely involve consultation with non‑members, which serves two primary goals: first, to educate non‑members about the ongoing issues and suggestions, and second, to collect insights from the wider community. SILL members would then work together to draft proposals, which they would then vote on.

The Epistemic Advantages of Lottocracy

Why think this lottocratic system is epistemically superior to electoral democracy? Guerrero highlights six advantages.5

First, a lottocratic system better addresses the problem of public ignorance. Introducing single‑issue legislatures significantly reduces the knowledge burden on participants, as they focus on one subject area, enabling them to make more informed decisions. The learning phase also ensures that participants become well‑versed in the relevant issues before making decisions.

Second, lottocracy mitigates the risk of capture by interest groups. The random selection of SILL members eliminates a major pathway for influence, as there is no electoral process for powerful interests to manipulate who gets chosen. Moreover, the absence of election campaigns means there is no need for SILL members to seek funding. Furthermore, offering a high salary to SILL members (and making it contingent on not being influenced by external interests) significantly reduces the pool of individuals willing to risk a guaranteed substantial income for uncertain bribes. Lastly, the regular rotation of SILL members makes it difficult to maintain influence over the system, as continuous investment in new members would be required, unlike in traditional systems where long‑term incumbents can be more easily co‑opted.

Third, lottocracy eliminates the electoral incentives that foster a short‑term bias. In this system, because individuals are selected through a lottery rather than elections, they are freed from the pressures of seeking re‑election and the need to claim immediate credit for their actions. Instead, they can focus on the long‑term implications of their decisions without being swayed by the need to secure voter approval in the near term. This may help with long‑term issues like climate change.

Fourth, lottocratic representatives have the opportunity for deeper, more extended engagement with the issues, which undermines the efficacy of purely emotional appeals and manipulative rhetoric. By providing ample space for thoughtful deliberation, the system is designed to promote decisions that are the product of comprehensive understanding and reasoned debate.

Fifth, the lottocratic system reduces the tendency for group attachments and social identities to influence political thinking. By eliminating elections, the focus shifts from candidate personalities and the “us‑versus‑them” mentality to substantive policy issues, fostering a less polarized, more cooperative political environment. By concentrating on single‑issue legislatures, lottocracy also allows for a more nuanced approach to governance, where common ground can be found more easily, and attention isn’t monopolized by highly divisive topics. This structure encourages collaboration and minimizes tribalism, leading to an improvement in the quality of political discourse.

Sixth, lottocracy enhances the descriptive representativeness of the legislative body by selecting members randomly from the jurisdiction. This ensures that the legislative assembly mirrors the jurisdiction’s ideological, demographic, and socioeconomic diversity more accurately than a body composed solely of those who can run successful election campaigns. This diversity leads to a richer pool of perspectives and experiences being brought to the table, thereby improving the epistemic quality of decision‑making.

Objections to Lottocracy

Having outlined Guerrero’s lottocracy system and its virtues, I’ll now turn to some challenges it faces.

First, lotteries raise concerns about competence. Can we really entrust legislative duties to a randomly selected group of citizens? Elected officials often have, or are perceived to have, specific political, legal, or policy expertise. Their professional backgrounds, education, and career trajectories are supposed to prepare them for the complexities of governance, enabling them to make informed decisions. Ordinary citizens have no such training.

In response, Guerrero suggests some mechanisms to mitigate these concerns, such as minimum educational requirements and enhancing public education. However, these measures might not suffice to ensure the decision‑making body’s overall capability to craft and enact effective legislation. Politically inexperienced citizens may need extensive training to undertake the complex, open‑ended, and tightly interconnected tasks involved in creating and assessing legislation.6 On the flip side, any proposed mechanism to address these concerns about incompetence may face the “reasonable disagreement” objection. Roughly, to amplify the voices of the competent, we first need to know what constitutes competence and then how to identify who the competent are. However, there is likely to be reasonable disagreement on both matters.

Second, lottocracy struggles with the complex trade‑offs necessary for competent decision‑making. Almost every policy solution competes for limited resources; thus, we must weigh fiscal trade‑offs with competing issues. However, Guerrero’s lottocratic system is organized around single‑issue legislatures. As a result, it may be too uncoordinated to work well. Legislative activity cannot be neatly confined to isolated domains. It’s unclear how citizens could make rational policy decisions without considering budgetary implications. For example, as Tom Malleson asks, “How could [lay citizens] come to a rational decision about whether it is better to provide expensive publicly provided day‑care centers, or cheap tax credits partially to support families providing their own child care, without knowing the relevant trade‑offs?”7 If SILLs are unable to weigh the ramifications of policy solutions for other issues beyond their agenda, this hampers competent deliberation and decision.

Third, lottocracy faces practical challenges in maintaining both synchronic and diachronic policy coherence. For example, how should we handle cases where an issue overlaps with two or more legislative policy areas? Should we allow two SILLs to merge in order to tackle specific policy challenges? As Daniel Hutton Ferris warns, “The use of multiple single‑issue legislatures is likely to lead to incoherent policy.”8

Fourth, the problem of identifying experts resurfaces. There must be a process by which a person is allowed to speak to a SILL as an expert. However, Guerrero says little about how these experts are to be selected. He writes, “Expertise might be recognized based on advanced degrees; years of professional experience; formal professional credentials from institutions with national or international accreditation; publication of research in independent, peer‑reviewed journals; and so on.” However, each of these markers of expertise is itself contestable.

Fifth, there is the problem of elite capture. While Guerrero argues that lottocracy reduces the risk of capture by interest groups, critics suggest the problem could actually be worse in a lottocratic system. For instance, lottocratic systems may be afflicted by a “revolving door problem.” As Dimitri Landa and Ryan Pevnick point out, lottocratic representatives know they will not hold office in the next term, irrespective of their performance. This gives them a freer hand than elected officials to “sell” their legislative influence to the highest bidder.9 Enforcing accountability may be difficult, particularly if representatives receive implicit, and rarely provable, kinds of quid pro quo (e.g., lucrative job opportunities).

Guerrero is aware of these challenges. In his new book, Lottocracy: Democracy Without Elections, he attempts to answer these concerns about citizen competence, budgetary trade‑offs, policy coherence, identifying experts, and elite capture, among other objections. For example, he challenges the assumption that elected generalist legislatures currently provide significant policy coherence, while arguing that the lottocratic system avoids the destabilizing policy swings caused by electoral cycles.10 He also suggests that creating a specialized Budget Assembly, analogous to Appropriations and Budget committees in generalist legislatures, would address concerns about resource allocation.11 While I cannot explore his responses in detail here, I encourage readers to consult his book for a comprehensive defense of lottocracy.

Open Democracy

In her recent book, Landemore introduces a revolutionary democratic model called “open democracy.” Similar to Guerrero’s lottocratic system, open democracy abolishes the familiar institutions of representative democracy, such as parliaments, parties, and elections. In an open democracy, it is ordinary citizens, not the elites, who occupy the center of political power.

Landemore proposes that we replace voting and elections with lottocratic mini‑publics, where a randomly chosen segment of the populace is tasked with representing and making decisions for the wider community. Instead of electing professional politicians into representative roles, leadership is assigned through a process similar to jury duty. Periodically, individuals are randomly selected to join a legislative body and fulfill their civic duty. During their term, they collaborate with others to address issues and steer the nation’s course. Once their term is over, they return to their ordinary lives and jobs.

What would open democracy look like in practice? The central institutional feature of open democracy is the “open mini‑public,” which Landemore describes as:

a large, all‑purpose, randomly selected assembly of between 150 and a thousand people or so, gathered for an extended period of time (from at least a few days to a few years) for the purpose of agenda‑setting and law‑making of some kind, and connected via crowdsourcing platforms and deliberative forums (including other mini‑publics) to the larger population.12

This legislative assembly would be at the center of a network of other mini‑publics, some focused on single issues, others generalist, operating at various levels. All mini‑publics would be staffed by randomly selected citizens rather than elected representatives.

Why random selection? It ensures that the group of representatives is a genuine microcosm of society at large, rather than being predominantly made up of corporate lobbyists, affluent individuals, or other elite groups. As John Adams wrote, these assemblies would allegedly provide “an exact portrait, in miniature, of the people at large.”13 According to Landemore, these mini‑publics would also be “open to the input of the larger public via citizens initiatives and rights of referral as well as a permanent online crowdsourcing and deliberative platform.”

What differentiates Landemore’s open democracy from Guerrero’s lottocracy system? Landemore favors a centralized, all‑purpose legislative assembly over Guerrero’s myriad of single‑issue mini‑publics. This preference arises from “the necessity of dealing with bundled issues in order to reach a coherent set of laws and policies.”14 As such, Landemore’s model may avoid the policy inconsistencies that could arise in Guerrero’s system. Moreover, open democracy incorporates more public input through crowdsourced feedback and occasional referendums, so people who aren’t currently governing will not feel excluded. By contrast, Guerrero’s lottocracy may offer fewer opportunities for citizens to engage politically.

As Landemore emphasizes, open democracy is not the same as direct democracy. The problem with direct democracy is one of scale: ordinary citizens cannot effectively deliberate all at once; deliberation is possible only in small numbers. Thus, representation is necessary to maintain a truly deliberative form of democracy. Although open democracy is a type of representative democracy, it is neither a form of “elite” rule nor does it require elections. At the heart of open democracy is the idea of citizen representation, where lay citizens represent other citizens.

Why abolish elections? Landemore suggests that the current crisis of democracy can be traced to a central flaw in the design of representative democracy: electoral representation. She argues that elections inherently favor the wealthy, educated, and charismatic, and they provide an unfair advantage to individuals based on race and gender. This “oligarchic bias” implies that ordinary citizens are regularly excluded from participation in law‑making, which violates core democratic values, such as inclusiveness and equality.15

These discriminatory effects also have epistemic costs. This idea follows from Landemore’s epistemic argument for democracy, according to which the rule of the many is often epistemically superior to the rule of the few. Specifically, a lack of cognitive diversity can hinder the collective intelligence of a group. Electoral parliaments will thus have limited epistemic potential due to a lack of diversity. (This echoes Guerrero’s concern.) Open democracy, by contrast, is more likely to identify problems and devise solutions, as its inclusiveness fosters greater cognitive diversity.

Furthermore, elections result in partisan politics, which stifles effective deliberation. Party allegiance often overshadows open‑minded engagement with different perspectives. When individuals emotionally identify with a political “team,” they are more likely to dismiss or undervalue the opposing side’s ideas, regardless of their merit. Partisan politics thus reduces the capacity for critical thinking and rational debate, as loyalty to the party becomes more important than seeking truth. According to Landemore, these inherent flaws in electoral systems call for a profound rethinking of how democratic institutions operate.

Open democracy could overcome these limitations. First, it more faithfully instantiates the ideal of popular rule by giving more decision‑making power back to the people. Second, it broadens participation among citizens, leveraging their collective wisdom for more informed choices. Third, the absence of partisan bias promotes productive deliberation unclouded by party loyalty. Finally, open democracy is less subject to the oligarchic or aristocratic bias of elections, which has purportedly contributed to the decay of democracy in recent years.16

Objections to Open Democracy

Open democracy raises several important questions. If citizens are not elected as representatives, are they truly democratic representatives? Does political equality arise solely from having equal opportunities for political power? Are lottocratic bodies sufficiently accountable to the public? Does open democracy demand too much of its citizens? These issues are important and fascinating, and Landemore attempts to address them.17 Here, I will focus specifically on epistemic challenges to open democracy.

Are Ordinary Citizens Incompetent?

A familiar objection is that, in a highly complex world, it is unwise to give amateur citizens more access to our central political institutions. Critics suggest that instead of empowering ordinary citizens, we should promote increased specialization and a division of labor to handle growing complexity.

Landemore provides three responses to this concern. First, there are reasons to believe that a large group of non‑experts can make smarter decisions than a group of experts, under the right conditions.18 Therefore, involving ordinary citizens in decision‑making would not necessarily lead to poor policymaking. Second, opening up democracy to political “amateurs” doesn’t imply sidelining experts and specialists. Rather, it suggests transitioning their role to advisors instead of primary decision‑makers, adhering to the principle of keeping “experts on tap, not on top.” Third, in situations of high complexity and uncertainty about effective solutions, it is likely best to distribute power equally and inclusively, ensuring we maximize the chances of accessing the right perspectives, information, and ideas.19

However, one might worry that randomly selecting citizens to serve on a fully generalist legislature places unreasonable epistemic demands on those chosen. Since these citizens typically serve only for a few years, it may be unrealistic to expect them to develop sufficient expertise across a wide range of policy areas, ranging from healthcare and agriculture to education and immigration. By contrast, the single‑issue legislatures proposed by Guerrero impose far less demanding expectations. By focusing on a single policy area, with support from expert testimony, citizens can narrow their scope of responsibility, allowing for more concentrated and informed deliberation.

If Numbers Trump Ability, Why Use Mini‑Publics?

According to Brennan, Landemore’s defense of open democracy is doubly puzzling.20 First, Landemore defends democracy by citing the collective intelligence of large groups. She is unconvinced by the critiques of democracy that suggest voter ignorance and irrationality lead to inferior political results. Yet, to justify open democracy on instrumental grounds, she must admit that existing representative democracies have flaws that lead them to perform badly. But then it becomes difficult for Landemore to assert that democracy with universal suffrage outperforms all epistocratic alternatives. Second, Landemore’s model of open democracy involves randomly selecting a small group of citizens to make political decisions. But if “numbers trump ability,” as she claims, then why limit ourselves to mini‑publics with few people?

In response to the second objection, Landemore could argue that Brennan has misunderstood the issue. While more heads are better than fewer, this doesn’t entail that electoral democracy with universal suffrage is wiser than open democracy with mini‑publics. In an electoral democracy, a diverse and large citizenry could make smarter decisions at the polls than a smaller group of supposed experts. However, an inherent feature of electoral democracy is that, beyond voting, most of the political decision‑making is primarily in the hands of a few elite representatives. These representatives may be more politically knowledgeable than the average citizen, but they are not a diverse group. Consequently, the decisions made by elected representatives are prone to epistemic shortcomings.

General Objections to Lottocratic Systems

Finally, I’ll consider two general objections to lottocratic systems. Although I will focus on Guerrero’s and Landemore’s accounts here, these worries generalize to any institutional proposal that advocates replacing elections and parties with smaller deliberative bodies.

Public Ignorance

A system of mini‑publics or SILLs could unintentionally promote ignorance among the general public, as they effectively eliminate mass participation and deliberation. In Guerrero’s lottocracy and Landemore’s open democracy, a small group would handle all democratic work, leading to less popular participation than in electoral democracy. This could discourage broader citizen engagement with politics. Even with numerous mini‑publics or SILLs, most citizens wouldn’t be actively participating at any given time due to the vastness of modern politics. The opportunity to serve on a mini‑public might be rare, possibly occurring only a few times in an individual’s lifetime, if at all. Consequently, politics may not occupy a regular and enduring place in the lives of most citizens. By contrast, partisanship and regular voting provide a daily stake in politics, motivating citizens to stay informed and engaged.

That said, public ignorance may be less concerning for these lottocratic systems compared to electoral democracy. The structure of mini‑publics ensures that those making decisions (i.e., lottocratic representatives) are sufficiently knowledgeable. While citizens not directly involved in decision‑making may lack relevant knowledge, this doesn’t necessarily affect the quality of political decisions. The deliberative process in mini‑publics and SILLs is structured to provide participants with access to expert insights, diverse perspectives, and ample time for reflection and discussion. This transforms participants from being part of the “ignorant public” to members of well‑informed assemblies. By contrast, public ignorance can wreak havoc in electoral democracies, since voters can (and do) make authoritative decisions based on ignorance.

The Problem of Blind Deference

A key attraction of lottocratic mini‑publics and SILLs is that they facilitate high‑quality deliberation (an epistemic dimension) while also “mirroring” the larger population as a kind of microcosm (a democratic dimension).21 However, lottocratic systems have been critiqued for bypassing the actual beliefs and attitudes of the citizenry. According to Cristina Lafont, lottocratic systems are objectionable because they require the general populace to blindly defer to the members of mini‑publics, which is inconsistent with the democratic ideal of self‑government.

Why must citizens blindly defer to mini‑publics and SILLs? In a lottocratic system, a randomly selected group is empowered to make decisions for the rest of the citizenry. The general public is therefore excluded from political decision‑making. Furthermore, the general public has no particular reason to assume that the decisions endorsed by the majority within these deliberative bodies would align with the judgments of the citizenry.22 As a result, the general populace cannot identify with the institutions, laws, and policies to which they are subject or endorse them as their own.23

Why think the decisions made by these lottocratic bodies wouldn’t reflect the values of the broader population? Lafont argues that while mini‑publics and SILLs aim for representation through random selection, the deliberative process is designed to transform the opinions of ordinary citizens into the considered judgments of lottocratic representatives. Consequently, participants in these systems would no longer “mirror” the wider public’s preferences or values. This transformation, while valuable for informed decision‑making, raises questions about the legitimacy of the outputs of mini‑publics and SILLs and their ability to genuinely represent the public’s will. According to Lafont, there will be a disconnect, or misalignment, between the opinions of the citizenry and the laws and policies to which they are subject.

Lafont is also concerned with the democratic legitimacy of decisions made by lottocratic deliberative bodies. Since participants in them are not elected representatives, their accountability to the wider population is limited. In an electoral system, by contrast, representatives have a direct responsibility to their voters; their decisions can be scrutinized, and they can be held accountable in subsequent elections if their actions do not align with the public’s will. This ensures that those directly tasked with legislation are suitably sensitive to the concerns of the citizens they claim to represent. While citizens must defer to the political decisions of elite politicians, they needn’t do so blindly. Instead, they delegate political decision‑making to others while maintaining some capacity to ensure that policies will be aligned with their values.

Finally, it might be naive to assume that a political community will reach better outcomes by merely bypassing the beliefs and attitudes of its citizens. If decision‑making power is given directly to mini‑publics, excluding the general populace, it hinders our ability to change hearts and minds, transforming citizens’ perspectives so they can endorse policies that are supported by better reasons.24 Therefore, even if mini‑publics produce the “right” outcomes, they may still “leave citizens behind” by failing to persuade them of the decisions’ reasonableness. As a result, we could frequently see situations where decisions endorsed by a majority within mini‑publics are opposed by the broader public majority. This disconnect could lead to frequent bottom‑up challenges, potentially stalling the legislative work of mini‑publics and destabilizing the political system.

In summary, lottocratic systems may conflict with the democratic ideal of self‑government, as they require citizens to blindly defer to the judgments of others. Additionally, they create a persistent disconnect between the considered judgments of “the few” and the opinions of “the many.” This misalignment could compromise the perceived legitimacy and stability of lottocratic systems: citizens might increasingly question the authority and relevance of decisions that do not seem to reflect their values or desires. That said, these concerns only address lottocratic systems where legislative power lies entirely in an allotted chamber, such as Guerrero’s lottocracy and Landemore’s open democracy. They do not speak against the use of mini‑publics in an advisory role. When used to enhance public debate without “shortcutting” it, mini‑publics can meaningfully enrich the democratic process.

Note: This post is an excerpt from Political Epistemology: An Introduction.

Aristotle 2017: 1294b.

Montesquieu [1748] 1989: II: 2.

Guerrero 2014: 155.

Guerrero 2021: 169-170.

Guerrero 2021: 172-178.

Bagg 2024: 93.

Malleson 2018: 411.

Hutton Ferris 2023: 8.

Landa and Pevnick 2021: 55–59.

Guerrero 2024: 251-254.

Guerrero 2024: 254–256.

Landemore 2020: 13.

Adams [1776] 1980.

Landemore 2020: 80, n1.

Landemore 2020: 76.

Landemore 2020: 220.

Landemore 2020: 81, 91–92, 98–104, 206.

Goodin and Spiekermann 2018; Landemore 2012a.

Brennan and Landemore 2022: 191–192.

Brennan and Landemore 2022: 269–271.

Fishkin 2009, 2018; Goodin and Dryzek 2006.

Lafont 2020: 116.

Lafont 2020: 3.

Lafont 2020: 30.

"This method was based on the belief that all citizens had an equal right to office and that random selection is more impartial than elections, which tend to favor the wealthy or well‑connected."

From what I can tell, this is the standard assumption among contemporary democratic theorists. And from what I am able to work out, there is good reason to think that it is wrong.

Sortition amongst the Greeks was more likely to be favoured in democracy because it was a way of constraining the power of the rich, who could otherwise disproportionately use their influence to control the constitution vis-a-vis the poor. After all, if office is assigned by lot, then it is pure luck, and the rich can't do things like e.g. buy votes (or equivalent, given that office is undertaken directly not through representation). If you are an ancient Greek living in a small city state, if democracy is to continue and to function tolerably well as a democracy, it needs to ensure that it *remains* a democracy, and that means that the many must not become extensions of the desires and ambitions of the few.

It is at times like this that reading Aristotle is I think really helpful. The ancient Greeks were really not like us. The central question at the heart of their constitutional arrangements was deciding who gets to make decisions, based on their class allegiances. The rich, or the poor? So it is not just that they did "direct" democracy, whereas ours is representative. It is that the nature of polis politics was explicitly about class based confrontation. Sortition was not about giving everybody an equal "right" participate, it was a mechanism for preserving democracy in the face of oligarchy.

I think modern democratic theorists are really missing a trick here...

I have the opposite view of Sortition: It is an excellent mechanism to chose among experts, and specially necesary for the supreme court:

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/PyqPr4z76Z8xGZL22/sortition

However, for human groups with a homogeneous degree of knowledge and a common training (that eases communication and the division of intellectual labor) the lottery is the best tool to achieve homogeneous, replicable and impartial decisions. Both the ancient Romans and John Rawls represent justice behind a veil of ignorance: the just decision is one that does not depend on proper names or special circumstances, but on the application of general laws and principles to the particular case.”